The Cold Start Problem

About

作者:Andrew Chen

Introduction

A Network of Networks

Foundational Questions

The Definitive Guide to Network Effects

The Cold Start Problem is the culmination of hundreds of interviews, three years of research and synthesis, and nearly two decades of experience as an investor and operator. It takes much of the knowledge and core concepts swirling inside the technology industry and frames them in the context of the beginning, middle, and end of a network’s life cycle. This is the core framework I’ll describe via the major sections of this book, along with examples, and providing an actionable road map for your own products.

Part I: Network Effects

1. What’s a Network Effect, Anyway?

The Billion Users Club

the Network Effect can be defined by breaking the term into its constituent parts—the “network” and the “effect.”

The “network” is defined by people who use the product to interact with each other. These networks are counterintuitive in that they connect people, but don’t own the underlying assets.

The “effect” part of the network effect describes how value increases as more people start using the product.

The questions to ask are simple: First, does the product have a network? And second, does the ability to attract new users, or to become stickier, or to monetize, become even stronger as its network grows larger?

Launching New Tech Products Today Is Incredibly Challenging

The technology ecosystem is downright hostile to new products—competition is fierce, copycats abound, and marketing channels are ineffective.

2. A Brief History

The Dot-Com Boom

Metcalfe’s Law

Metcalfe’s Law The law is defined below: The systemic value of compatibly communicating devices grows as a square of their number.

Said plainly, each time a user joins an app with a network behind it, the value of the app is increased to n^2. That means if a network has 100 nodes and then doubles to 200, its value more than doubles—it quadruples.

Metcalfe’s Flaws

Metcalfe’s Law is a simple, academic model that fails the test of real-life messiness.

Meerkat’s Law

Yes, it’s true: social animals have network effects, too.

The Math of Meerkats

Allee threshold—where the animals would be safer and thus ultimately grow faster as a population. In other words, Allee’s population curves describe a sort of ecological version of the network effect.

As the population increases, eventually there is a natural limit based on the environment—often called a carrying capacity. For social animals like meerkats and goldfish, overpopulation looks like this, starting flat, then hitting a tipping point before growing quickly and then saturating and falling once again:

When Populations (and Networks) Collapse

The Allee Curve at Uber

Meerkat’s Law versus Metcalfe’s Law

While the terms are different, the core concepts and the math are the same: The Allee effect → The Network Effect Allee Threshold → Tipping Point Carrying capacity → Saturation

3. Cold Start Theory

The Framework

I call this framework Cold Start Theory, named for the first and most important stage in building network effects.

There are five primary stages:

1. The Cold Start Problem

The Cold Start Problem Solving the Cold Start Problem requires getting all the right users and content on the same network at the same time—which is difficult to execute in a launch.

Atomic Network Atomic Network focuses on building an “atomic network”—that is, the smallest possible network that is stable and can grow on its own.

2. Tipping Point

Tipping Point as a network grows, each new network starts to tip faster and faster, so that the entire market is more easily captured.

To win a market, it’s important to build many, many more networks to expand into the market.

3. Escape Velocity

Escape Velocity The Escape Velocity stage is all about working furiously to strengthen network effects and to sustain growth.

the Engagement Effect, which increases interaction between users as networks fill in

the Economic Effect, which improves monetization levels and conversion rates as the network grows.

I redefine it so that it’s not one singular effect, but rather, three distinct, underlying forces: the Acquisition Effect, which lets products tap into the network to drive low-cost, highly efficient user acquisition via viral growth

4. Hitting the Ceiling

Hitting the Ceiling This is driven by a variety of forces, starting with customer acquisition costs that often spike due to market saturation, and as viral growth slows down

5. The Moat

The Moat The final stage of the framework focuses on using network effects to fend off competitors, which is often the focus as the network and product matures.

Five Stages

This is the Cold Start Theory. It is made up of five stages for creating, scaling, and defending the network effect, and aims to provide a road map for any new product team—at a startup or larger company—to leverage in their work.

Cold Start Theory is meant to apply to a large set of companies in the technology industry: video platforms, marketplaces, workplace collaboration tools, bottom-up SaaS products, social networks and communications apps, and more.

Many of these ideas generalize beyond the world of mobile apps, as my friend Naval Ravikant, a noted investor and entrepreneur, has observed: Humans are the networked species. Networks allow us to cooperate when we would otherwise go it alone. And networks allocate the fruits of our cooperation. Money is a network. Religion is a network. A corporation is a network. Roads are a network. Electricity is a network.

Part II: The Cold Start Problem

4. Tiny Speck

When you start a new product with network effects, the first step is to build a single, tiny network that’s self-sustaining on its own

The second step was a private beta-testing period with friends of the company, where Stewart would personally reach out, try to get them to use Slack, and iterate to add features and improve the experience.

Each of these beta customers formed an atomic network—a stable, self-sustaining group of users who can drive a network effect

Introducing the Cold Start

It’s a myth that network effects are all powerful and positive forces—quite the opposite.

because when people show up to a product and none of their friends or coworkers are using it, they will naturally leave. What solves this? “The Atomic Network”—the smallest network where there are enough people that everyone will stick around

These networks often have “sides,” whether they are buyers and sellers, or content creators and consumers. Generally one side of the network will be easier to attract—this is the easy side of the network

The Hard Side” of a network—the small percentage of people that typically end up doing most of the work within the community To attract the hard side, you need to “Solve a Hard Problem”—design a product that is sufficiently compelling to the key subset of your network

When the Cold Start Problem is solved, a product is able to consistently create “Magic Moments.” Users open the product and find a network that is built out, meaning they can generally find whoever and whatever they’re looking for. The network effects kick in, and the market hits its Tipping Point as users start coming to you.

5. Anti-Network Effects

Anti-Network Effects Anti-Network Effect Anti-network effects are the negative force that drives new networks to zero.

For Slack, it doesn’t make sense to use the product until your colleagues are also on the platform. For Uber, you can’t use the service until there are enough drivers, who won’t drive until there are enough rides.

What’s Enough?

Stewart Butterfield, CEO of Slack, answered this question for me: Slack works with just 2 people, but it takes 3 to make it really work. There are long-running 3 person groups that are stable—that’s the minimum required to be called a customer.

for Slack it was approximately 2,000 messages—where they’ll stick around and keep using the product:

How many users does your network need before the product experience becomes good? The companies to do an analysis on the size of their networks (on the X-axis) plotted against a set of important engagement metrics (on the Y-axis).

Eric Yuan, CEO of Zoom, said to me: You just need two people. One who wants to call someone else and have a conversation—that’s enough for Zoom to be useful for both people and to have them keep using it.

Chris Nakutis Taylor, one of the early general managers at Uber, describes their importance: ETAs were always terrible to start. +15 min in some areas, especially in the suburbs. There was another key metric. Get ETAs down under 3 min on average as quickly as possible while covering the whole city. If you could get ETAs, unfulfilleds, and surge down quickly, you’ll have a healthy market.

William Barnes, another early GM who was one of the first fifty employees and launched Los Angeles, describes the early ad hoc calculation: The strategy was “let’s get a bunch of cars on the road” and try and get their ETAs and the request conversion rate (the % who purchase a ride) to reasonable levels. In LA and other big cities, the goal was to try to get 15–20 concurrent online cars on the road at the same time. LA’s launch was notoriously expensive because we worked hard to get that all in West Hollywood at launch.

For new products, it’s important to have a hypothesis for the size of your network even before you begin. Communication apps can be 1:1, so the network is small, and you can plan accordingly. Contrast that to products that are highly asymmetrical, with content creators and viewers, or marketplaces with buyers and sellers—these are likely to require a much bigger number to hit the threshold, and require a much bigger effort to get started. The size of an initial network helps determine a launch strategy.

The Antidote to the Cold Start Problem

Solving the Cold Start Problem requires a team to launch a network and quickly create enough density and breadth such that the user experience can improve in leaps and bounds

Density and interconnectedness is key.

The solution to the Cold Start Problem starts by understanding how to add a small group of the right people, at the same time, using the product in the right way

6. The Atomic Network—Credit Cards

For companies like Uber that exist both offline and online, it might seem obvious that a city-by-city approach is the right strategy. But there’s a history of products like Tinder and Facebook growing from tight-knit college communities, as well as B2B companies like Slack that grow team by team within a larger company

Launching the First Credit Card

Credit cards have network effects for the same reasons that marketplaces do: they aggregate consumers, merchants, and other financial institutions as a multi-sided network

The Atomic Network

It needs to have enough density and stability to break through early anti-network effects, and ultimately grow on its own

Many of them are counterintuitive: The networked product should be launched in its simplest possible form—not fully featured—so that it has a dead simple value proposition

Why Starting with a Niche Works

Chris Dixon, my colleague at a16z, summarized the idea in an essay titled, appropriately, “The next big thing will start out looking like a toy.”

The next big thing will start out looking like it’s for a niche network.

Picking Your Atomic Network

maybe on the order of hundreds of people, at a specific moment in time.

My advice: Your product’s first atomic network is probably smaller and more specific than you think.

The general managers and Driver Operations had an internal tool, called Starcraft—referring to the real-time strategy game popular at the time—that allowed them to click on a group of cars, text them “Go to the train, lots of riders!” and direct them in real time.

The Power of Atomic Networks

Growing city by city, campus by campus, or team by team is a surprisingly powerful strategy

7. The Hard Side—Wikipedia

The Volunteers Who Built Wikipedia

Even though there are hundreds of millions of users, there are only about 100,000 active contributors per month

This relationship exists everywhere. There are nearly 100 million riders on Uber, but just a few million drivers

The Easy Side versus the Hard Side

Hard sides exist because there are tasks in any networked product that just require more work, whether that’s selling products, organizing projects, or creating content. Users on the hard side have complex workflows, expect status benefits as well as financial outcomes, and will try competitive products to compare.

the hard side of the network is game developers.

the hard side of the network creates a ton more value. At the extreme like Valve’s Steam

Consumers are generally the easy side of a network In a less extreme example of value creation, the best Uber drivers will work many times more hours than the average driver

The Hard Side of Social Content Apps

In a widely read essay called “Creators, Synthesizers, and Consumers,” Bradley Horowitz, now a vice president of product at Google, described the 1 percent of users who create versus everyone else: 1% of the user population might start a group (or a thread within a group) 10% of the user population might participate actively, and actually author content whether starting a thread or responding to a thread-in-progress 100% of the user population benefits from the activities of the above groups (lurkers)

1/10/100 rule 1-10-100 Rule the 1 percent of highly engaged users is extremely valuable.

there is a “power law” curve where the 20 percent of top influencers and content creators end up with the vast majority of engagement.

Evan Spiegel, CEO and cofounder of Snap, described his understanding of the content creation pyramid for Snap and Instagram, versus TikTok: You can imagine a pyramid, if you will, of internet technology or communications technology, where the base of the pyramid—the very broad base—is self-expression and communication. And that’s what Snapchat is really about. Talking to your friends, which is something everyone is comfortable doing. They just express how they feel. As the pyramid gets narrower, you have the next layer, which is status. Social media in its original construct is really about status, representing who you are, showing people that you’re cool, getting likes and comments. Those sorts of things. And that’s less accessible to the broad base of humanity, and has a narrower base of appeal. [There’s a] more limited frequency of engagement, because people only do some things that are cool once a week or once a month, and not every day. At the top of the pyramid, which I think is represented by TikTok, is really talent. People who have spent a couple hours learning a new dance, or think about a funny new creative way to tell a story. They’re really making media to entertain other people. I think that’s even narrower.

The more difficult the work needed to be part of the hard side of a network, the smaller the percentage of users who will participate.

The social feedback loop is a core concept because the creator/viewer network is so ubiquitous as a network structure.

it’s all about the content creators. It’s important to focus on this tiny slice of users so that messaging, product functionality, and business model are all aligned to serve them.

Wikipedia’s Teeny, Tiny Hard Side

8. Solve a Hard Problem—Tinder

The answer is by building a product that solves an important need for the hard side.

The Problem of Too Many Love Letters

Tinder’s cofounder, Sean Rad, about how Tinder innovated on the previous generation of products. He described the combination of new ideas: The older dating sites made it feel like you were doing work, like you were inside the office. You’d go and do work emails during the day, then go home and write more messages at night. Only to prospective dates rather than work colleagues. Tinder was different—it made dating fun. You could sign up without filling in a bunch of forms. It’s visual, you just swipe back and forth, and you could take five minutes to do it while you were waiting in line or something like that. It’s a form of entertainment.

Tinder started by making everyone connect their Facebook, so that we could show the number of mutual friends you had, which built trust

The Hard Side for Marketplaces Is Usually the Supply Side

For marketplaces, the hard side is usually the “supply” side of the network, which refers to the workers and small businesses who provide the time, products, and effort and are trying to generate income on the platform

Nights and Weekends

how do you find a problem where the hard side of a network is engaged, but their needs are unaddressed? The answer is to look at hobbies and side hustles.

What people are doing on their nights and weekends represents all the underutilized time and energy in the world.

But once an atomic network is established, the hard side of the network is willing to extend their offerings and services to go into the next vertical.

The Hard Side of Dating Apps

9. The Killer Product—Zoom

Networked Products versus Everything Else

Why Networked Products Love to Be Free

New Shifts in Behaviors and Computer Platforms

10. Magic Moments—Clubhouse

This is the Magic Moment, when a product can deliver its core value A product that hasn’t yet solved its Cold Start Problem will fail to deliver any magic in its early days.

The Clubhouse Story

Clubhouse launched in 2020 Before Clubhouse, there were other apps focused on connecting people through audio. Years before, Rohan had worked on Phone-a-friend, an app to connect groups of friends over audio. People could quickly start a podcast, record with hosts, edit, and publish, all in the same app. Talkshow had all the tools in one place. Talkshow, which made it much easier to produce podcasts. People could quickly start a podcast, record with hosts, edit, and publish, all in the same app. Talkshow had all the tools in one place.

how do you get to something magical faster? they needed to radically simplify. To make sure creators had a lightweight experience, it would be ideal to easily create content with people already hanging out in the app—that way, it avoided the coordination problem of getting your friends into an app at the same time.

Great products take time to figure out, and Clubhouse is no different. It was an overnight success that took years.

The Opposite of the Magic Moment

The Magic Moment is a nice concept, but it would be even more useful if you could measure it. The way to best do this might be surprising—you start with the opposite of magic, the moments where the network has broken down, and you start solving the problem from there.

After the Cold Start Problem

When a networked product finally starts to generate Magic Moments, it feels really good. Often, this is called Product-Market Fit.

Part III: The Tipping Point

“Tipping Point,” when a product can quickly grow to take over the whole market.

11. Tinder

USC Campus, 2012

The answer to this conundrum was the University of Southern California, which in many ways was an ideal place for Tinder to get started…Both Sean and Justin had gone to USC, and more important, Justin had a younger sibling going to the college at the time. And they concocted a plan: Tinder would work with Justin’s younger brother to throw a birthday party for one of his popular, hyperconnected friends on campus, and use it to promote Tinder.

There was one catch with the party: First, you had to download the Tinder app to get in. We put a bouncer in the house to check that you had done it.

The Tinder team built one atomic network, but soon figured out how to build the next one—just throw another party.

Introducing the Tipping Point

To begin the discussion of the Tipping Point, I’ll start with a prominent strategy, “Invite-Only,” that is often used to suck in a large network through viral growth.

Another method to tip over a market is with a “Come for the Tool, Stay for the Network” strategy.

some products can always just spend money to build out their network, with a strategy of just “Paying Up for Launch.”

If the hard side of the network isn’t yet activated, a team can just fill in their gaps themselves, using the technique of “Flintstoning”

In the end, all of these strategies require enormous creativity. And to close out the Tipping Point section of the book, I introduce Uber’s core ethos of “Always Be Hustlin’”—describing the creativity and decentralized set of teams, all with its own strategies that were localized to each region.

12. Invite-Only—Linkedin

Yet this constraint is at the heart of the so called “invite-only” strategy for launching a product. And for Gmail, Linkedin, Facebook, and many other networked products, it has worked. Why?

Invite mechanics work like a copy-and-paste feature—if you start with a curated network, and give them invites, that network will copy itself over and over automatically.

Linkedin thus adopted a more flexible positioning as a professional networking service

The Welcome Experience

Invite-only mechanics provide a better “welcome experience” for new users as well. To explain why, imagine arriving at a large dinner party. A good friend welcomes you at the door, and as you step in, you see acquaintances, close friends, and a number of new people who’ve been curated to be absolutely fascinating

Mathematically, it tends to work even better than that—the most connected people tend to be invited earlier, and in turn they tend to invite other highly connected people

Hype and Exclusivity

You might ask, if invite-only is so great, why isn’t it used more often? There are good reasons. It’s often seen as risky, because it can kill the top-line growth rate of your product. It requires you to build a lot of extra functionality, so that people who newly sign up are connected properly with people around them

Curating a High-Quality Network

How Invite-Only Products Curate Their Networks

13. Come for the Tool, Stay for the Network—Instagram

Come for the tool, stay for the network” is one of the most famous strategies for launching and scaling networks. Start with a great “tool”—a product experience that is useful even for one user as a utility

Hipstamatic was created by two friends from Wisconsin, Ryan Dorshorst and Lucas Buick, and showed the enormous appetite people would have for mobile photography in the coming years. In 2010, in its inaugural “Apps of the Year,”

Importantly, Instagram was built with a network from day one. It had user profiles, a feed, friend requests, invitations, and many other features of a modern social product. Instagram launched on October 6, 2010, to the App Store, and at the end of the first week, it had been downloaded over 100,000 times. Six months after the app’s launch, an article on Techcrunch by analytics firm RJ Metrics analyzed data from Instagram’s APIs and concluded that 65 percent of users were not yet following other people on the network. in 2011, tennis player Serena Williams and singers Drake, Justin Bieber, and

Britney Spears would all post their first photos. Popular Instagram accounts of cute dogs, travel destinations, and models would eventually turn into the “influencers” that would define the platform. These influencers, celebrities, companies, meme accounts, and many others would all join to create content, building network density and increasing engagement.

Similarly, over time, the “tool” part of the product—the photo filters—have waned in importance, as users often post photos with the “#nofilter” tag. A recent analysis has shown that the vast majority of photos—82 percent—had no filter used at all. Eight years after its initial launch, network effects had fully taken over for the utility of photo editing—it’s more network, and less tool.

How Great Tools Help Tip Entire Markets

“Come for the tool, stay for the network” circumvents the Cold Start Problem and makes it easier to launch into an entire network—with PR, paid marketing, influencers, sales, or any number of tried-and-true channels

Marketplaces are generally networks, not tools, from the start. But for a large class of products centered on content creation, organization, and reference, it can be a winning strategy

Underlying Patterns for Tools and Networks

Each provides a tool oriented around content editing and hosting—whether that’s a video, photos, resumes, or documents. The tool is combined with a network that allows people to interact with the content and by extension, other people.

Group a few other products that have a tool/network pairing, and some clusters start to emerge:

Why This Strategy Works, and When It Doesn’t

Next I will discuss how, for some products, you can just go at it direct: use money. Pay up for the launch, and subsidize usage of the network until it starts to work. It’s expensive, but it can work.

14. Paying Up for Launch—Coupons

eventually want to figure profitability out. But for networked products, in the earliest stages, sometimes it makes sense to spend—often wildly—to pay up for growth. The goal is to get the market to hit the Tipping Point, driving toward strong positive network effects, and then pull back the subsidies

Coca-Cola was soon flowing in every state across the country

Coupons were invented in 1888 by John Pemberton and Asa Candler, cofounders of the Coca-Cola Company

The common wisdom was, “If you have a chicken and egg problem—buy the chicken.”

The next part of scaling the initial traction was to recruit a lot more drivers. This is where the power of leveraging the network helped tremendously using referral programs

referral programs (“Give $200, get $200 when a friend signs up to drive”) over time structures like “Do 10 trips and get an extra $1 per trip”

15. Flintstoning—Reddit

Reddit is a perfect example of how Flintstoning can be used early, and how it evolves from manual work into automation at scale

a16z is an investor in Reddit, and over the years, I’ve gotten to know Steve and the team

All of these dummy accounts looked and acted like real users

Flintstoning the Hard Side of the Network

Reddit’s use of Flintstoning is similar to the strategy used by companies like Yelp and Quora—to fill in the hard side of the network, which were also content creators

Services like DoorDash and Postmates Flinstoned by showing a large selection of restaurants, regardless of whether those restaurants had actually signed up

B2B marketplaces exist in real estate, freight, labor, and many other large multibillion-dollar industries, spawning billion-dollar startups like Flexport and Convoy

but the first few years are just people powered.

Cyborg Startups Cyborg Startup “cyborg startups,” because they combine humans (who are executing tasks manually) with a team of software engineers who automate as much as they can over time

Automation Can Scale Flintstoning

Flintstoning can be thought of as a spectrum: Fully manual, human-powered efforts Hybrid, where software suggests actions to take, but people are in the loop Automated, powered by algorithms

Famously, PayPal built bots that would automatically buy and sell items on eBay, but insist on transacting only with PayPal

The Extreme—Platforms and Their Applications

Ideally, outside game developers will build for the new platform, but they often don’t know how to take advantage of the new functionality

To break through this Cold Start Problem, Nintendo spared no expense in the Switch launch, simultaneously releasing the latest installments of their classic Mario and Zelda franchises—each have sold tens of millions of units

The games industry calls this “first-party content,” and it can be a serious investment. Over the years, Microsoft Xbox has taken this strategy to an extreme, buying a large number of studios and bringing them in-house.

this isn’t a common strategy for social networks, it’s also not crazy. In recent years, we’ve seen players like YouTube in video and Spotify in podcasts begin to license and create more first-party content to accelerate their services.

Exit Strategy

In other words, once the Cold Start Problem is solved, it’s important to let the network grow and stand up on its own—and turn off Flintstoning entirely.

16. Always Be Hustlin’—Uber

Travis would regularly say to the product teams, “Product can solve problems, but it’s slow. Ops can do it fast.”

The Importance of Creativity

the Ops team would call local limo service companies one by one

Hustle as a System

A driver referral program like “Give $200, Get $200” could be bumped up and turned into a New Year’s branded “Start your new year right—Give $300, Get $300” campaign

In the end, you might ask—did Uber Ice Cream really help? As an individual stunt, it may not have had a massive impact on the company

Most important, Uber created a system to quickly identify, execute, and iterate on these concepts—it was supported by an entrepreneurial team culture, robust software tooling, and an understanding that each city would be its own Cold Start Problem.

Enterprise Hustle

In a research study called “How today’s fastest growing B2B businesses found their first ten customers,” startup veteran Lenny Rachitsky interviewed early members of teams from Slack, Stripe, Figma, and Asana.

It’s a huge advantage to have a strong personal network in B2B, which you can also build by bringing a connector investor or joining an incubator such as YC. Getting press is rarely the way to get started

many productivity products begin by launching within online communities—like Twitter, Hacker News, and Product Hunt—where dense pockets of early adopters are willing to try new products. In recent years, B2B products have started to emphasize memes, funny videos, invite-only mechanics, and other tactics traditionally associated with consumer startups

One of the most common types of advice we give at Y Combinator is to do things that don’t scale… . The most common unscalable thing founders have to do at the start is to recruit users manually. Nearly all startups have to. You can’t wait for users to come to you. You have to go out and get them.

Graham goes on to cite examples from Stripe and Meraki as well as consumer startups like Facebook and Airbnb, which employed this philosophy.

The Gray Area

Dropbox’s folder sharing features were used early on for pirating movies and music

When this happens, do you try to fix the loopholes or add more controls, potentially impacting the usability of the product

Like many Cold Start examples, embracing the gray area created issues in the early days

Uber 1.0 Cultural Values

Uber 1.0 Cultural Values:

- Make Magic

- Superpumped

- Inside Out

- Be an Owner, Not a Renter

- Optimistic Leadership

- Be Yourself

- Big Bold Bets

- Customer Obsession

- Always Be Hustlin’

- Let Builders Build

- Winning: Champion’s Mindset

- Principled Confrontation

- Meritocracy and Toe-Stepping

- Celebrate Cities

Part IV: Escape Velocity

17. Dropbox

Dropbox had initially been built on Amazon’s cloud platform, and the product was growing so fast that the hosting bills had become very expensive.

To kick off an effort to generate more revenue, a cross-functional Growth and Monetization team was convened…growth teams have emerged across the industry as a focused way to scale products toward Escape Velocity. In parallel, the team began to explore the data, looking for critical insights that made one user more valuable than another. Not every user is the same, nor is every network the same.

Dropbox’s insights on this were profound: some users joined Dropbox as part of the “come for the tool” strategy—but stayed with the tool without increasing their engagement by sharing folders and documents with others. In contrast, the ones who used Dropbox for collaboration and sharing—the network features—became significantly more valuable over time. Dropbox’s users could be divided into High-Value Actives (HVAs) and Low-Value Actives (LVAs), which was useful as a quality indicator.

Data could be misleading sometimes, too. In the early days, Dropbox was growing so fast that it was often hard to do analyses on what types of content people were putting in their folders.

First, the team surveyed users and realized that many High-Value Actives were upgrading their Dropbox accounts for use at work

The right question was: Which files did people tend to go back and edit or move, again and again? What types of files did multiple users within a network tend to share, collaboratively edit, and interact with?

Introducing Escape Velocity

When new products see success and start to scale, it’s often called hitting “Escape Velocity. In the Escape Velocity phase, the company needed to continue scaling the use base, and ultimately build a real revenue-generating business.

To make it concrete enough for product teams to act upon, I argue that there are a trio of network effects: Engagement, Acquisition, and Economics.

The Engagement Effect is what happens when a product gets stickier, and more engaging, as more users join.

The Economic Effect Network effects can help improve business models over time, in the form of improved feed algorithms, increased conversion rates, premium pricing, and more.

The Acquisition Effect on the other hand, is the network effect that powers the acquisition of new customers into your product—in other words, viral growth.

18. The Trio of Forces

Escape velocity is often described as a kind of end state, the moment when a product becomes dominant in the market, where everything gets easier.

Three Systems Underlying the Network Effect

the network effect is not one effect. Instead, the network effect is a broader umbrella term that can be broken down into a trio of underlying forces:

- the Acquisition network effect

- the Engagement network effect

- the Economic network effect

The “Acquisition Effect” is the ability for a product to tap into its network to acquire new customers.

The “Engagement Effect” describes how a denser network creates higher stickiness and usage from its users—it is a more specific form of the classic description of network effects that I covered at the beginning of the book, “the more users that join the network, the more useful it gets.” In turn, these elevated use cases drive key metrics, as more engagement directly maps to number of sessions per user, or the number of days per month that you’re active in the product.

The “Economic Effect” is the ability for a networked product to accelerate its monetization, reduce its costs, and otherwise improve its business model, as its network grows.

The Growth Accounting Equation

I use Engagement, Acquisition, and Economic network effects as the core taxonomy for the reason that they map to the key outputs that product teams care most about: active users and revenue, and the leading indicators to these metrics.

Gain or loss in active users = New + Reactivated − Churned

This month’s actives = Last month’s actives + gain or loss

19. The Engagement Effect—Scurvy

In the modern usage, users are often divided into separate groups—called cohorts—which then allow them to be measured separately.

The Sad Truth about the Stickiness of New Products

Retention is the most critical metric in understanding a product, but most of the time, the data is not pretty.

In collaboration with Ankit Jain, a former product manager at Google Play, I published an essay titled “Losing 80% of mobile users is normal,” which illustrated the rapid decay that happens right after a new user signs up to a product. Of the users who install an app, 70 percent of them aren’t active the next day, and by the first three months, 96 percent of users are no longer active. Data from analytics company comScore, revealed that people spend 80 percent with just three apps51—and I’m sure you can guess which ones.

As a rough benchmark for evaluating startups at Andreessen Horowitz, I often look for a minimum baseline of 60 percent retention after day 1, 30 percent after day 7, and 15 percent at day 30, where the curve eventually levels out.

Their unique ability to tap into the Engagement network effect lets them drive up retention over time—first, by creating new use cases as the network develops; then by reinforcing the core “loop” of the product; and lastly, by reactivating churned users. I’ll unpack how these levers work.

How New Use Cases Drive More Engagement

The first lever comes from the Engagement Effect’s ability to raise retention curves by layering on use cases.

As an example, when a small team first adopts a chat product like Slack—before the rest of the company does—they might just use a few channels to discuss items relevant to the team. But as more of the company also onboards employees onto the product, new use cases are unlocked.

What starts as infrequent and noncommittal usage often deepens into daily usage.

to do this, teams have to do what Dropbox did and find a way to segment higher versus lower value users. Monetary value might not be the right segmentation—it might be something else, like frequency, lifetime value, use cases, or some other defining characteristic.

For example, Linkedin’s user base was tiered based on frequent usage, as my good friend Aatif Awan—the former vice president of growth at LinkedIn—describes: At LinkedIn, we segmented our users as: Active the last 7 days out of the last week Active the last 6 days Active the last 5 days … and so on. This let us dig into each segment separately and understand their needs, motivations, and what it would take to move them up in engagement

But it’s often not all the same lever—depending on the type of users, and their motivations and intent, different approaches will work. Awan describes this in the context of LinkedIn’s strategy to increase frequency: This is where the A/B Test becomes so valuable. Just as James Lind did with her scurvy experiment, users can be randomly divided into separate cohorts and given different experiences. A correlation like “High-value LinkedIn users connect to other users at a higher rate than low-value users” can then be converted into a real lever.

The question then becomes how to get these users to take the various actions that will make them higher value. This usually happens in the form of educating users.

In Dropbox’s case, this segmentation revealed that a user who has installed the product across multiple devices—home and work computers, or on their mobile devices—is more valuable than someone who just has a single device and uses the service for backup.

Engagement Loops

Engagement network effect makes products stickier over time, but how?

Engagement Loop describes how users derive value from others in a network in a step-by-step process.

Users need to trust the loop to rely on it. If the network is too small or too inactive and the loop breaks, then users will be less likely to use it in the future.

The Escape Velocity phase is about accelerating these loops, by making each stage of the loop perform better.

Back from the Dead

The Engagement network effect has the superpower of being able to reactivate Churned Customer, which in turn grows the active user count.

data I’ve seen from startups, a typical product might only have 25–50 percent of its registered users active in any given month, expressed as a ratio of actives divided by signups. Traditional products that lack networks often struggle with this, because they rely on spammy emails, discounts, and push notifications to entice users back. A notification that a close friend just joined an app you tried a month ago is a lot more engaging than an announcement about new features. And the more dense the network is around a churned user, the more likely they are to receive this type of interaction.

The Impact of the Engagement Effect

tech companies can reason by analogy: create user cohorts by levels of engagement, and analyze what differentiates high value users from lower value ones.

20. The Acquisition Effect—PayPal

This is one of the most magical, explosive forces in the technology world: viral growth.

The PayPal Mafia

One example is the embeddable player for YouTube

PayPal started with a product called FieldLink, which let people send and receive money on Palm Pilots and other PDAs (personal digital assistants) but importantly, no internet access FieldLink was not going to work, and in the search for a new idea, PayPal was born.

early days PayPal’s growth was still slow. The value proposition was vague, since the web was still in its infancy. Users didn’t quite know why they would pay each other—the product had not found its killer use case. eBay PowerSeller changed all of that. The seller had designed a “We accept PayPal” button by themselves, and asked to use it on their auction listings There was natural virality emerging, and it was up to the team to supercharge it The eBay community was a tight-knit network, and PayPal quickly spread. The initial product had fewer than 10,000 users. Within a few months, PayPal had 100,000 users. A few months after that, 1 million. Within a year, 5 million

most viral products ever created—like WhatsApp—have been able to generate over 1 million installs per day, without paid marketing.

Viral growth builds on the power of networks to acquire users, often free of charge.

Product-Driven Viral Growth

This is the Product/Network Duo at work again, where the product has features to attract people to the network, while the network brings more value to the product.

Amplifying the Viral Factor, One Step at a Time

For example, consider this process: A new user hears about a service, signs up, finds value in it, and shares the product with their friends/colleagues, who also sign up. These new users then repeat the same steps—this is the viral loop.

Uber’s viral loop for drivers involved a referral program that was exposed during the onboarding process.

Measuring the Acquisition Network Effect

1000 users download the new app. A percentage of these users invite their colleagues and friends, and over the next month, 500 users download and sign up—what happens next? Well, those 500 users then invite their friends, and get 250 to sign up, who create another 125 sign-ups, and so on. Pay attention to the ratios between each set of users—1000 to 500 to 250. This ratio is often called the viral factor, and in this case can be calculated at 0.5, because each cohort of users generates 0.5 of the next cohort A higher ratio is better, since it means each cohort is more efficiently bringing on the next batch of users

If you increase the viral factor of your product to 0.6, then the product will 2.5x the users you bring. At 0.7, then the product will 3.3x the users you bring. The real magic starts to happen as the viral factor starts to approach 1. After all, at a viral factor of 0.95, 1,000 users show up and then bring 950 of their friends, who will then bring 900, and so on—ultimately the amplification will be 20x. This is the mathematical expression of when a product “goes viral” and starts growing incredibly fast.

Acquisition Can’t Exist without Engagement

The Impact of the Acquisition Effect

21. The Economic Effect—Credit Bureaus

Credit Bureaus

Economic network effect, which is how a business model—including profitability and unit economics—improves over time as a network grows.

The Network Effects of Lending

These bureaus tended to combine into larger bureaus over time because of what’s often described as a “data network effect.” When a bureau works with more merchants, it means more data, which means the risk predictions on loans will be more accurate.

Efficiency over Subsidy

launching a new network often requires subsidies for the hard side, which are paid back over time.

when Microsoft introduced a new livestreaming service to compete with Twitch, it guaranteed Ninja, a streamer with millions of followers, a deal worth tens of millions.

eventually combining with Didi after burning nearly $50 million a week in rider and driver incentives to launch the market. This effort totaled over a billion dollars of cash burn that year.

focused first and foremost on “Efficiency over Subsidy”—improving Uber’s unit economics.

The math around Uber’s marketplace subsidies looked like this, at a high level: Offer a $25/hour guarantee to drivers

- A small network might provide 1 trip per hour

- Let’s say drivers earn, on average, $10/trip

- This means drivers can earn $10/hour, so to hit the guarantee, the company must subsidize an additional +$15/hour to make up the difference

- This means the “Burn per Trip” is $15. Ouch!

Uber could provide far more trips to drivers: Same guarantee: $25/hour to drivers

- However, a larger network provides 2 trips per hour to drivers

- At $10/trip, the larger network generates $20/hour—much better!

- At $20/hour and a $25/hour guarantee, the subsidy is only $5/hour

- In other words, only $2.50 Burn per Trip

This is a clear example of the Economic Effect, where a larger network has much higher efficiency than a small one—the company burns significantly less per trip, because the network can deliver more demand on an hourly basis. It also means that a bigger network could give even larger incentives, allowing it to efficiently win over drivers who are the hard side of the network.

Higher Conversion Rates as the Network Grows

Dropbox’s High-Value Active Users is an example of this—users were found to upgrade into paid subscriptions when they had collaborative use cases with their coworkers, like shared folders and collaboration around documents.

networked products like marketplaces and app stores—though for different reasons. When more sellers are part of a marketplace, there’s more selection, availability, and comprehensive reviews/ratings—meaning people are more likely to find what they want, and each session is more likely to convert into a purchase.

The Impact of the Economic Effect

The Economic network effect, alongside its siblings in acquisition and engagement, provide a strong defense against potential upstarts.

Economic Effect means that the leading network often has a better business model. Products with a strong Economic Effect are able to maintain premium pricing as their networks grow, because switching costs become higher for participants who might be looking to join other networks.

However, this trio of network effects does not create permanent invincibility in the market. While a large network often enjoys years of uncontested dominance during the scaling phase, eventually it gets harder. So hard, in fact, that growth might slow to zero.

Part V: The Ceiling

22. Twitch

But as a product reaches scale, its growth curve eventually reaches a point where it teeters on the edge between expansion and contraction—bursting into expansion during some phases, and then contracting in others.

Ship the right innovative features, and the ceiling is pushed off—only to return again awhile later in a different form.

CEO and cofounder Justin Kan described the situation:

About the end of 2010, the company turned profitable. We did a ton of hard work to make it profitable, but we were at an impasse. We weren’t growing very much. Actually, we weren’t growing at all. When something’s not growing on the Internet, it’s basically on the brink of declining, precipitously.

Thus, Xarth.tv—yes, that’s what Twitch was originally called—was born. Unfortunately for the team, the board of directors hated the plan. This new plan would turn a profitable startup into one losing millions of dollars, and it wasn’t yet obvious it would work.

As Emmett would recount to me at Twitch’s purple-clad offices several years later, this new strategy had some key differences to Justin.tv’s original one:

We did a lot different with Twitch than Justin.tv. The biggest thing was to focus on streamers, whereas originally it was more about the audience. This meant we worked on tools for streamers, which we improved over time. Making money was important to streamers, even small amounts, so we added tipping features.

All of these product changes made it easier for the best and most popular streamers to quickly gain a following.

The new features and functionality were built on the observation that the atomic network for Twitch could be as few as just one streamer and one viewer watching them.

Kevin added:

The real magic starts to happen once [you] have enough followers on Twitch, and you consistently have viewers every time you start streaming. Then every session on Twitch becomes fun, since there’s always an audience. But it’s even more fun to make money. Once there’s enough viewers, then you’ll eventually make your first dollar. This is a real aha moment—our streamers talk about how making even $20 or $50 a month is an eye-opener. But then build enough of an audience, and eventually, it’s possible to “go pro” and just work by streaming full-time.

after Twitch’s launch that the top streamers began to make $300,000+ per year.

Within a month after launch, Twitch had 8 million unique viewers, and within a year after that, it had doubled to 20 million. And then doubled again, and so on, so that today it is one of the most highly trafficked websites in the world.

It’s not just consumer companies that face this—workplace products and bottom-up SaaS startups use their network effects to grow virally, but eventually saturate their initial market of startups and early adopters. Then they need to learn how to sell into the enterprise to build the next phase of their business. We see this all the time at Andreessen Horowitz, where my colleague David Ulevitch says: In the early days, startups often see success as other startups and small businesses adopt their product—this is the “bottom-up” distribution model that has propelled Slack, Zoom, Dropbox, and many others. Problem is, smaller customers are always churning out because they’re price sensitive, running out of money, and changing their business model—sometimes all three! Larger enterprise customers, on the other hand, are sometimes harder to break into but can grow revenue over time as more and more users adopt it within a company. Thus it’s natural for B2B startups to begin with a bottom-up sales motion but eventually add expertise to sell into enterprises.

Introducing the Ceiling

It happens for a variety of reasons, including market saturation, degradation of marketing channels, overcrowding, spam, and so on.

In “Rocketship Growth,” I’ll start by defining success—what it means to be on track, versus hitting the ceiling.

First among the causes of slowdown is “Saturation.” At the same time this is happening, the network itself is changing. While the hard side evolves, the rest of the network is changing as well. And finally, I describe how discovery of relevant people and content becomes hard—I call this the “Overcrowding” dynamic within networks.

23. Rocketship Growth—T2D3

In the United States, there are roughly 6 million new businesses started each year…These startups are then referred to about 1,000 active venture capital firms…there are about 5,000 venture capital investments per year available to new and early-stage startups…only 1 in 20 venture-backed startups end up with the > 10x exits the industry is focused on.

The team at Horsley Bridge—a high-profile investor in venture capital funds—has shown that industry-wide the failure rate of venture-backed startups is over 50 percent. There are many reasons why this happens, but generally, the outcome is the same: they stop growing, peter out, and never achieve success.

The biggest companies each year eventually come to employ over a hundred thousand people, like Amazon, Oracle, Microsoft, Apple, Intel, Google, and others. They represent nearly 20 percent of the S&P 500 and several of them became worth more than a trillion dollars at the start of 2020. These outsized returns are why Stanford researchers have ascribed 57 percent of the value of the US stock market to companies initially backed by venture capital.63 These companies employ over 4 million people, investing $454 billion on R&D. Incredible.

The Rocketship Growth Rate

Rocketship Growth Rate the precise pace at which a startup must grow to break out.

Hitting a $1 billion Valuation generally requires at least $100 million in top-line Annually Recurring Revenue, based on the rough market multiple of 10x revenue.

Neeraj Agarwal, a venture capitalist and investor in B2B companies, first calculated this growth rate by arguing that SaaS companies in particular need to follow a precise path to reach these numbers:

- Establish great Product-Market Fit

- Get to $2 million in ARR

- Triple to $6 million in ARR

- Triple to $18 million

- Double to $36 million

- Double to $72 million

- Double to $144 million.

The first phase, in which the team initially gets to Product-Market Fit, takes 1–3 years…SaaS companies like Marketo, Netsuite, Workday, Salesforce, Zendesk, and others have all roughly followed this curve.

Add on the time to reach the rest of the growth milestones, and the entire process might take 6–9 years.

after year 10, the company might still be growing quickly, though it’s more common for it to be growing 50 percent annualized rather than doubling.

For those seeking venture capital, it is a pretty standard minimum bar to get to $1 billion in valuation over ten years.

The Rocketship Growth Rate was originally developed for SaaS software companies where the business model is powered by a subscription, and so for companies like Dropbox, Zoom, Slack, and DocuSign it’s directly applicable.

Rocketship Growth Rates for Marketplaces

for marketplace companies, gross merchandise value (GMV) or net revenue is often used—that maps to that Valuation.

An equation to calculate the target growth rate is handy here. The equation looks like this:

\(Rocketship\ growth\ rate = (\frac{target\ revenue-starting\ revenue}{starting\ revenue})^\frac{1}{years}\)

Or filling in our numbers: Rocketship growth rate = (($200M − $1M) / $1M)^(1⁄6) = 2.4x

Why the Rocketship Trajectory Is Tough

Rocketship Growth Rate is very hard. And even while each year’s goal tends to triple or double, a company will simultaneously face countervailing forces—saturation of the market slows down growth, marketing channels degrade in performance, and product development never keeps up with user demands. The cardinal rule is that growth rates tend to drop over time, even as more investment is poured into adding employees, building the product, and servicing customers.

The Good News, and the Bad

The reason is straightforward—teams tend to use all the obvious growth levers they can in the first few years, which quickly run out over time.

Networked products, on the other hand, have a massive advantage—they can tap into their network effects to fight the slowdown. For example, while the steady decline of marketing channels is inevitable, teams can amplify viral growth by optimizing sign-up funnels, recommendations for friends to invite, and so on.

24. Saturation—eBay

Success comes with an inevitable problem: market saturation.

Eventually this stops working because nearly everyone in the target market has joined the network, and there are not enough potential customers left.

Eventually this stops working because nearly everyone in the target market has joined the network, and there are not enough potential customers left. From here, the focus has to shift from adding new customers to layering on more services and revenue opportunities with existing ones.

It was in 2000, and for the first time ever, eBay’s US business failed to grow on a month-over-month basis.

Jeff shared what the team did to find the next phase of growth for the company:

Launching “Buy It Now” was a large change that touched every transaction, but the eBay team also innovated across the experience for both sellers and buyers as well.

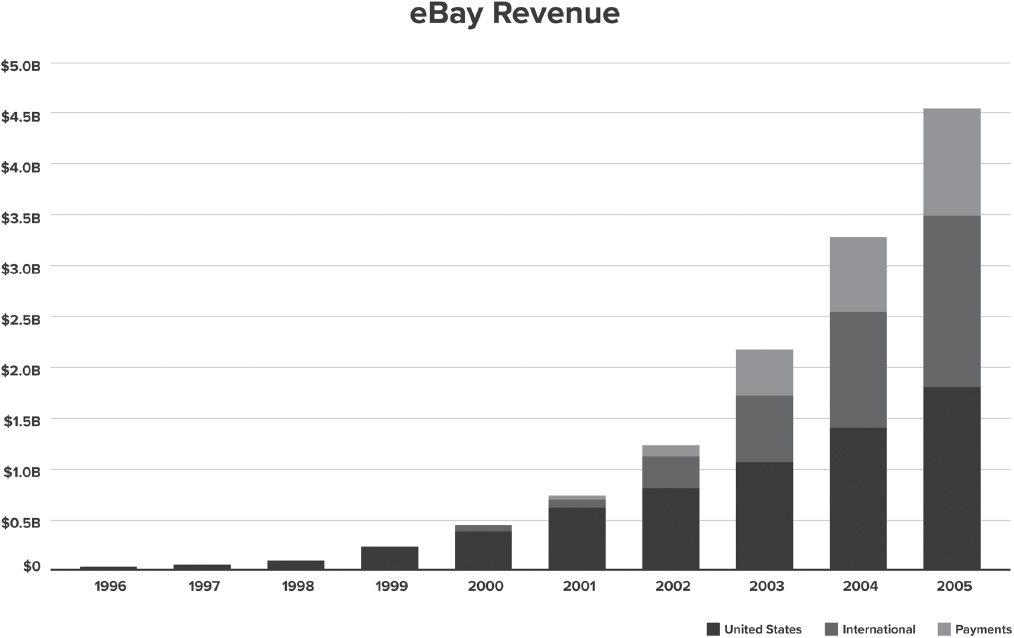

eBay Revenue

eBay Revenue

Network Saturation versus Market Saturation

Although this entire phenomenon is often called market saturation…I think of it as network saturation, not just market saturation. Here’s how I define this term: the 100th connection for any given participant is likely less impactful than the first few, and as the network gets more dense over time, its associated network effects become less incrementally powerful.

Social apps have a similar dynamic, where each additional friend connection is not as valuable as the previous one. In an internal memo to the Snapchat team, CEO Evan Spiegel reported on the diminishing returns of connections: Your top friend in a given week contributes 25% of Snap send volume. By the time you get to 18 friends, each incremental friend contributes less than 1% of total Snap send volume each.

Snapchat team, CEO Evan Spiegel reported on the diminishing returns of connections:

Your top friend in a given week contributes 25% of Snap send volume. By the time you get to 18 friends, each incremental friend contributes less than 1% of total Snap send volume each.

New, Adjacent Networks

Understanding these adjacent networks is key, so that they can be targeted one by one to expand and fight saturation.

Understanding these adjacent networks is key, so that they can be targeted one by one to expand and fight saturation. My friend Bangaly Kaba, formerly head of growth at Instagram, called this idea the theory of “Adjacent Users.” He describes his experience at Instagram, which several years post-launch was growing fast but not at rocketship speed:

Our success was anchored on what I now call The Adjacent User Theory. The Adjacent Users are aware of a product and possibly tried using it, but are not able to successfully become an engaged user. This is typically because the current product positioning or experience has too many barriers to adoption for them. While Instagram had product-market fit for 400+ million people, we discovered new groups of billions of users who didn’t quite understand Instagram and how it fit into their lives.

Bangaly describes this approach:

When I started at Instagram, the Adjacent User was women 35–45 years old in the US who had a Facebook account but didn’t see the value of Instagram. By the time I left Instagram, the Adjacent User was women in Jakarta, on an older 3G Android phone with a prepaid mobile plan. There were probably 8 different types of Adjacent Users that we solved for in-between those two points.

New Formats

The beauty of something like eBay’s “Buy It Now” and “Stores” efforts is that they still fundamentally tap into the same network of buyers and sellers, but provide a new interaction that might better support new use cases.

New Geographies

Layering on new geographies—as eBay did by adding international regions—is another way to build up the layer cake.

Regional expansion is easier when networks grow into directly adjacent networks

However, there are failure cases as well. A highly urban market like San Francisco possesses many unique factors: lots of early adopters, a high cost of living, a mostly urban environment, and a very educated consumer market

Layering on growth from faraway geographies is far harder. This usually requires the team to start their network from zero once again, on top of all of the additional work: localizing content, finding local partners, implementing new payment methods, and potentially iterating on the product concept itself—because sometimes the idea doesn’t fully translate.

Laying on completely new international markets is hard because it generally requires a combined effort from many different team functions.

Why Fighting Market Saturation Is So Hard

The solutions to market saturation might sound straightforward—add new geographies, support more formats and business models, and other tips that sound like common sense.

25. The Law of Shitty Clickthroughs—Banner Ads

The Law of Shitty Clickthroughs The Law of Shitty Clickthroughs says every marketing channel degrades over time. This means lower clickthrough, engagement, and conversion rates, regardless of if you’re talking about email, paid marketing, social media, or video. This is a core reason why products hit growth ceilings—when marketing channels stop performing, the growth curve starts to bend downward.

Consumers first experienced banner ads on Hotwired, the first commercial web magazine.

The advertisers launched the first campaign that included a banner ad that asked the viewer, “Have you ever clicked your mouse right HERE? You will.”

Today, banner advertising clickthrough rates usually hover around 0.3–1 percent, but the first ads ever had incredible engagement: 78 percent at the start!

It’s not just online advertising that followed this trend—email did, too.

ClickZ, an industry blog, published a graph showing that over a nearly decade time span, email marketing clickthrough rates dropped from 30 percent to under half that—13 percent.

The same can be found for nearly all growth channels over time.

Degrading the Network

The degradation of marketing channels is an existential threat to a product’s network effects.

Layering on New Growth Strategies

When new products launch, there are usually one or two acquisition channels that work—but they might not scale. In Dropbox’s case, the initial wait list was formed by users who watched the announcement video about the product.

The best practice is for products—whether they have network effects or not—to constantly layer on new channels.

The key for a new product team is to understand which channels best fit its product, and to hire the relevant people who’ve already done it.

For workplace/B2B products, the focus will often turn toward adding a direct sales channel in combination with the other various “bottom-up” consumer-like acquisition channels, so that it all works in an integrated way. There is sometimes low-hanging fruit. Often, it’s as easy as looking at all the users who are signing up or who are active, and checking out their email domains to figure out which companies to sell into. Or maybe just asking these users for their company name and team size—and then start emailing them to sell. Another quick fix is to add a “Contact us” tier of service on the pricing page. At the same time, run a parallel effort that emphasizes content marketing, events, and other programs that drive more top of funnel leads. Build a growth team that can score individual accounts and add life cycle triggers so that the sales team sees when the product reaches a certain footprint inside an organization. In doing all of this, multiple channels can be combined into a broader strategy.

new B2B startups have started to embrace referral programs, memes, emojis, video clips, and other tactics previously reserved for consumer products.

Tapping into the Acquisition Network Effect

26. When the Network Revolts—Uber

The Hard Thing about the Hard Side

A well-organized revolt by the major members of its hard side can kill a product entirely.

The numbers are similarly concentrated: Slack’s S-1 filing showed less than 1 percent of Slack’s total customers accounted for 40 percent of the revenue, and Zoom’s indicated that 30 percent of revenue came from just 344 accounts, again less than 1 percent of their customer base.

The numbers are similarly concentrated: Slack’s S-1 filing showed less than 1 percent of Slack’s total customers accounted for 40 percent of the revenue, and Zoom’s indicated that 30 percent of revenue came from just 344 accounts, again less than 1 percent of their customer base

About half the top iOS apps are developed by a small group of elite developers: Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Amazon, and a few others. Just twenty apps drive 15 percent of all app downloads!

The most organized YouTube channels and Instagram influencers might start out as individuals, but eventually scale their production so that their millions of viewers see professionally created content. Reddit has these dynamics within moderators, who organize the largest communities with 20 million subscribers each! However, look further down the list and the numbers rapidly fall off in exponential fashion, such that a top 98th percentile community—ranked 20,000 out of over 2 million subreddits—has just a few thousand subscribers.

A networked product generally wants to nudge its ecosystem toward professionalization, because it helps scale the hard side

The company might offer training, documentation, and monetization

Up-front investment to try to professionalize the supply side early on in a network’s development inevitably comes with risk. In a well-publicized misstep for Uber, the company sought to expand its supply side by financing vehicles to provide cars to potential drivers who didn’t own vehicles, a program called XChange Leasing

XChange Leasing unfortunately lost $525 million and failed to professionalize the driver side of the market. The problem was, it attracted drivers highly motivated by money—usually a positive—but who didn’t have high credit scores for good reason

However, I argue that there’s no choice but to embrace this.

How Professionalization Happens

Professionalization happens in two ways: homegrown professionals, and off-network professionals

When a network’s biggest members become large, they can often become high-scale, investor-backed startups on their own.

When a network becomes large, rich, and diverse, it’s often described as an “Economy”—you may have heard about the Gig Economy, the Attention Economy, the Creator Economy, and so on.

No Choice but to Scale

What might have been a $70 Craigslist ad to recruit a driver in the early days eventually became $1,000+ per active driver from every direction—paid marketing, referrals, even TV and radio ads.

It needed to grow the market, and onboard a larger and more mainstream segment of users. This segment of drivers required more education, more vetting, and more encouragement on how they should interact with riders

Embrace the professionalization of the hard side, and reap the benefits of increasing scale.

27. Eternal September—Usenet

Created in the early days of the internet in 1980, Usenet was the first worldwide distributed discussion system, hosting newsgroups like talk.politics, rec.arts.movies, rec.crafts.winemaking, and a hundred other topics.

Early internet users even made up a term, called “Godwin’s Law”—the observation that every heated digital conversation devolves into comparisons with Nazis—to describe the vicious debates that happened on Usenet in the 1980s.

Context Collapse

Let’s use a story to describe how it happens—this one from Adam D’Angelo, CEO of Quora and ex-CTO of Facebook. He explains how it affects social and communication products: When you first join a social network with your close friends, it’s easy to use it a lot. You might post photos and comments all the time—full of in-jokes and shared stories. You and your friends like it so much you invite your other friends, and then their siblings, too. And so on. But eventually, photos and content meant for your close friends might attract comments from people you don’t know well. Your parents get invited, and maybe your teachers, or your boss. Those photos of a party you went to might get you in trouble.

Networks of Networks … of Networks

Products like iMessage or WhatsApp give us a clue. Messaging apps are resistant to context collapse. You talk to your dozen or so friends and family, and even if the network adds millions more people, it doesn’t change your experience.

In other words, not all networked products experience context collapse as rapidly as others.

The Power of the Downvote

Usenet’s Collapse, in Hindsight

28. Overcrowding—YouTube

Too many videos on YouTube is a specific case of a broader phenomenon of overcrowding, which can hurt network effects and ultimately make a product unusable.

The Early Days of Organizing Videos

YouTube as a dating site didn’t last long, and within a few weeks

The YouTube team rolled out solution after solution to solve overcrowding, but focused on the simple ones first—displaying a list of recently uploaded videos, followed by a popularity-based sort, and eventually country segmentation.

The Rich Get Richer’

Overcrowding works in a different way for creators than for viewers. For creators, the problem becomes—how do you stand out?

Eventually, the problem becomes, how does a new member of the network break in?

The Power of Data and Algorithms

In the years following the acquisition, Steve described the company’s focus very simply: “We were just trying to keep up with all the traffic.”

One notable example of this is the ever present “People You May Know” or “Friend suggestions” feature

TikTok’s relevance algorithms make sure that even as hundreds of millions of videos are added over time, creators will still be matched with viewers who want to consume their content—and vice versa. “Data network effects” are often invoked as a path for networks to solve relevance and overcrowding issues that emerge over time.

Algorithms Aren’t a Silver Bullet

To me, the key learning from the YouTube story is the journey that every networked product has to take. When they started out, they needed very little organization, but as the network grew, more and more structure was applied—first by editors, moderators, and users—and then by data and algorithms. The earliest iterations weren’t sophisticated, just whatever got the job done. Algori54-thms came later, and even years later, keeping the network healthy is still an everyday battle.

Part VI: The Moat

29. Wimdu versus Airbnb

If your product has network effects, your competitors likely have them, too—which can create a dangerous situation.

Wimdu was a direct copy of Airbnb focused initially on the European market, and from day one, it was a scary competitor—it launched with $90 million in funding, the largest investment in a European startup ever, and within less than one hundred days, the company already hired over 400 people and had thousands of properties on its marketplace. At that point, Airbnb was only two and a half years old, had 40 employees, and had raised a small venture capital round. It only supported payments in USD, no European currencies, and hadn’t been translated to any languages beyond English.

When Airbnb first launched, there were already several adjacent competitors. First, VRBO…but the product UI was less polished, with more friction to list and transact. VRBO was later merged with HomeAway, and more important, the network focused on vacation rentals located in out-of-the-way destinations rather than Airbnb’s early focus on shared spaces within dense urban cities…Another product, Couchsurfing, already existed as well, and was an indirect competitor, albeit a peculiar one. Founded in 2003 as a nonprofit, Couchsurfing allowed for people to crash on each other’s sofa while traveling but did not require payment.

By mid-2011, Wimdu was aggressive in taking on the European market…automated side, Wimdu built bots that would scrape listings—mirroring descriptions, photos, and availability so that if hosts wanted to maintain listings on both platforms…there were reports from the community that sometimes the listings were just fake…On the ground, Wimdu would pose as guests and rent from Airbnb hosts, and during the process try to convince them to also list on Wimdu…the company built over 50,000 listings and was on its way to $130 million in gross revenue in its first year of operations.

It took just two years for Wimdu to unravel. Incredibly by 2014, it was laying off employees and accepting that it had lost leadership in the European market. Eventually, through several rounds of M&A, all the employees were laid off in 2018.

Michael Schaecher, an early employee at Airbnb (#17) who headed up some of the international efforts in the competitive response, said of Wimdu’s strategy:

All supply isn’t created equal. Wimdu’s top 10% of inventory was at the bottom 10% of Airbnb’s. They went for numbers, but recruited large property owners that managed hundreds of units in the form of low-end hostels. They went the easy route and would get 1000 listings via 10 property owners, but the experience for customers was disappointing. In the early days at Airbnb, we would always talk about creating a positive “Expectations Gap.” In the early days, when we were new, guests go in with low expectations, but then would be blown away by the experience. You need this high NPS to get people to tell their friends, and it makes hosts more likely to join too. Our competitors who took shortcuts couldn’t deliver here.

Introducing the Moat

the moat, I will describe what happens when networks compete with other networks, and why this form of competition is so unique

To introduce the nature of network-based competition, I describe why it’s high-stakes, where the loser can go to zero while the victor taps into its network effects to win the market—this is the “Vicious Cycle, Virtuous Cycle.”

One of the core strategies in network-based competition is “Cherry Picking.”

The moat is about a successful network that defends its turf, using network effects in a perpetual battle against smaller networks trying to enter the market.

30. Vicious Cycle, Virtuous Cycle

Warren Buffett popularized the concept of the competitive Economic Moat, as he described his investing strategy:

The key to investing is not assessing how much an industry is going to affect society, or how much it will grow, but rather determining the competitive advantage of any given company and, above all, the durability of that advantage. The products or services that have wide, sustainable moats around them are the ones that deliver rewards to investors.

It’s the difficulty of cloning their network that makes these types of products highly defensible.

In the modern era, cloning software features is usually not the hard part

Because Buffett generally invests in low-tech companies like See’s Candies or Coca-Cola, the moat he refers to is often a strong brand or a unique business model.

But once Airbnb has reached Escape Velocity in a market, the Cold Start Problem creates the defense against new entrants. After all, every new competitor entering the city will need to solve the Cold Start Problem and build up the same density—as hard as it was for your product to go from zero to a Tipping Point, it will be even harder for competitors starting from a disadvantage.

This is literally the moat, and reframes the Cold Start Problem for Airbnb’s competitors

The Battle of Networks

lean toward “winner take all.” When one product emerges as the winner in an atomic network, that’s just the group choosing their favorite app. But repeat that enough times, and that becomes the playbook for a product to win across the entire market—and that’s a monopoly

But how does the competitive playbook work in a world with network effects? First, I’ll tell you what it’s not: it’s certainly not a contest to see who can ship more features

it’s often the dynamics of the underlying network that make all the difference

Network-based competition is unique, and has its own dynamics

Your Competition Has Network Effects, Too

To figure out a response, it’s important to acknowledge a common myth about defensibility and moats: that somehow, network effects will magically help you fend off competition

Effective competitive strategy is about who scales and leverages their network effects in the best way possible.

Network Collapse

David versus Goliath

Startups have fewer resources—capital, employees, distribution—but have important advantages in the context of building new networks: speed and a lack of sacred cows

31. Cherry Picking—Craigslist

Craigslist is a classifieds listing site that is an embodiment of a paradox.

a long line of startups have cherry-picked some of its most valuable audiences—famously referred to as the “unbundling of Craigslist.”

Craigslist should not be thought of as a single, monolithic network built on a unified classifieds product, but rather as a network of networks—the people who use the Seattle Craigslist are not the same as users in Miami.

Every dominant network might seem invincible, but the networks-of-networks framing argues that some parts of the network are weaker than others.

The opportunity to unbundle these larger networks requires both building the necessary product features to support these splinter communities and also taking the direct action to message, advertise, or otherwise convince members of the larger horizontal community to shift over.

Finding the Soft Spot

The question is, which atomic network do you pick?

As another example, let’s examine Snapchat. The product’s photo messaging features could be seen as just a feature of a larger social network product since, at the time, photos were one of many media types shared on Facebook, Twitter, MySpace, and other platforms.

Switching over Entire Networks