The Sales Learning Curve

About

Author: Mark Lesli, Charles A. Holloway

Intro ATTACH

Yet in our 25 years of experience with start-ups and new-product introductions, we’ve found that hiring a full sales force too fast just leads the company to burn through cash and fail to meet revenue expectations.

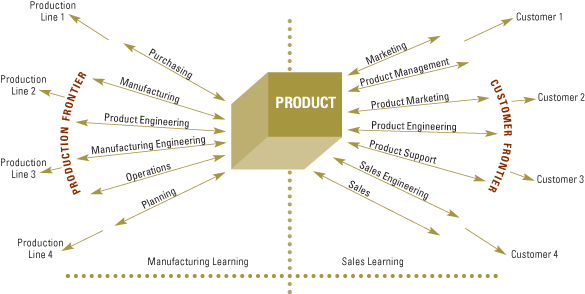

The concept of a learning curve is well understood in manufacturing. Employees transfer knowledge and experience back and forth between a production line and the purchasing, manufacturing, engineering, planning, and operations departments. Over time, the entire process becomes more effective: The more times a process is repeated, the more efficient it becomes and the lower its cost.

Instead of following conventional sales wisdom, the firm should focus first on organizing itself so it can learn from customers and respond to them.

the sales learning curve as a framework for helping managers and investors develop thoughtful launch strategies, plan resource allocation more accurately, set appropriate expectations, avoid disastrous cash shortfalls, and reduce both the time and money required to achieve a profit.

The New-Product Sales Challenge

Twenty-five years ago, the major risk in creating a company (or in launching a brand new product from an established company) was the feasibility of the technology. Managers believed: “If we can build it, they will come.” Today, the product development cycle is more predictable, thanks to the greater availability of subcomponents and robust development tools. So the biggest risk for most companies has shifted from getting the product to work to getting it to market. Entrepreneurs increasingly must ask: “When we build it, will they come?”

But if start-ups apply conventional sales wisdom to new-product launches and add sales capacity too quickly, the result is often disappointing revenue growth and a cash shortfall. That’s because the conventional wisdom fails to address a number of challenges involved in creating markets for unfamiliar products: the time required to educate customers about the offering and learn how they will use it, the inevitable design modifications needed to deliver a robust product that will fully satisfy customers, the identification and resolution of service issues, the development of a repeatable sales model, the selection of appropriate market positioning, and the design of effective sales incentives. Here’s a case in point.

Midcourse correction at a start-up.

Scalix, a software company that develops e-mail and calendaring programs hosted on Linux…Microsoft Exchange was originally designed for work groups and had never been upgraded to efficiently support large organizations…they aimed to cut total cost of ownership by 50% to 60%…Scalix launched its product, based on Hewlett-Packard’s OpenMail system, in July 2003…Its initial strategy was simple: Recruit a high-powered sales leader with enterprise experience and sell directly to CIOs at large companies.

encountered a number of unexpected problems.

- it became evident that the CIO was not the primary decision maker for purchasing e-mail systems…the people who would be responsible for keeping the system up and running on a daily basis—rejected Scalix’s solution.

- many large companies needed to get more comfortable with Linux before they would run e-mail on it.

- an entirely different order and perhaps the thorniest. Scalix learned its product was not quite ready for prime time.

In mid-2004, it overhauled its go-to-market strategy to hit the Linux evangelist and early adopter community first, with a particular emphasis on smaller targets in the higher education and public sectors, where Linux acceptance was strongest.

Breaking new ground at an established company.

What the Organization Needs to Learn

Every business goes through a unique learning process, and each industry, company, and product has a different set of drivers.

It develops gradually: The company makes initial assumptions, which are modified iteratively as feedback comes in from early customers. The modified offering reaches even more customers, whose further feedback hones the product, the message, and the sales efforts—accelerating the company’s progress along the learning curve.

The Sales Learning Curve

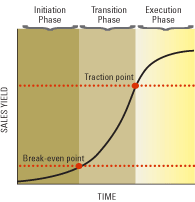

Progress along the sales learning curve is measured in an analogous way: The more a company learns about its product, market, and sales process, the more efficient it becomes at selling, and the higher the sales yield. “Sales Yield” is defined as the average annual sales revenue per full-time, fully trained and effective sales representative. Typically, sales yield for a new product starts out slowly, accelerates for a while, and then flattens out as the product matures, in a classic S-shape curve.

For many new-product launches, the sales yield never reaches expected levels, or even the break-even point, resulting in cash shortfalls and premature death for promising products.

Sales Force Planning for Launch

the sales learning process unfolds in three distinct phases—the initiation phase, the transition phase, and the execution phase—as the exhibit “Ramping Up the Learning Curve” shows. The gateways from one stage to the next correspond to two markers of profitability level—the break-even point and some targeted level of steady sales, which we call the “traction point.”

The initiation phase. ATTACH

This phase begins when the product is ready to hit the market, that is, when it has been beta tested, and lasts until the break-even point—that is, when sales yield reaches a point where revenue per sales rep equals the fully loaded cost per sales rep. Typically, during this time, few customers will be willing to consider buying the product, and those that do will require significant incentives.

dysfunctional to assign large sales quotas in the initiation phase. sales team should be encouraged to focus instead on learning as much as they can about how customers will use the product so they can support engineering, product marketing, and marketing communications in perfecting both the offering itself and the go-to-market strategy and programs.

It’s also inefficient to hire too many sales reps in this phase. A small sales force not only keeps costs down but is more effective in supporting other parts of the company. Typically, three to four salespeople are enough to start the learning process and to make sure that the problems encountered aren’t just the result of a bad hire.

The transition phase.

Once the sales yield equals the fully loaded expense per sales rep, it’s safe to assume you’ve moved into the transition phase. Still, we’ve found that a useful rule of thumb is to consider a sales yield of twice the fully loaded cost per sales rep as the end of the transition phase. By this point, the company should have a pretty good idea of what to expect in terms of steady state sales yield for the product.

In the transition phase, sales management should focus on developing a repeatable sales model, refining market positioning, and adding sales capacity at a rate commensurate with the rise in the slope of the curve.

The execution phase.

sales reps can be hired as rapidly as the company’s management and financial constraints will allow.

The Role of Marketing

Product marketing and marketing communications should ideally be the center of learning activities during the initiation phase. Marketing leadership is responsible for bridging the gap between customers, sales reps, and the engineering organization.